Engender blog

GUEST POST: Who says what? A breakdown of gender bias in news topics and reporting

Today we're publishing the next in a series of blogs from the current student placements Engender is hosting from the University of Strathclyde Applied Gender Studies and Research Methods course.

Today we're publishing the next in a series of blogs from the current student placements Engender is hosting from the University of Strathclyde Applied Gender Studies and Research Methods course.

In the second of three posts, Kirsty Rorrison continues research into gender bias in political news reporting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Here, she looks specifically at the breakdown of bias in topics and authors, as well as whose voices are missing in the reporting of the pandemic. You can read Kirsty's first post here.

As my placement with Engender is nearing its end, I have finally completed my research on gender, COVID-19 and media. In this blog post, I’m going to discuss what I found out in my investigation and why it was crucial that I delved a bit deeper into this topic. As I mentioned in my previous post, my main area of interest in this research has always been the ways in which women in politics are represented. However, I also wanted to look at how other women, and more broadly gender, appeared in news coverage of coronavirus. For this research, I ended up coding 108 news stories. I took note of the topic, the gender of the journalist, and the identity markers of every person mentioned in each article. I wanted to see where gender appeared in news coverage, whether this related to the kinds of topics being discussed, the journalists who wrote about them or the people mentioned in articles. In this blog post, I will outline what my analysis revealed about journalists and news topics - in other words, who is writing, and what are they writing about?

[Figure 1]

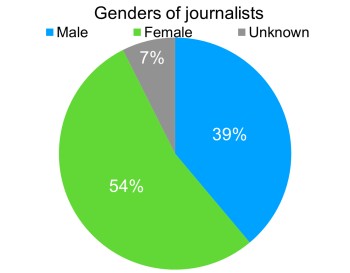

I was surprised to find a fairly even split between male and female journalists in my sample [Figure 1]; in fact, women were actually writing about COVID-19 more than men. At first glance, I thought this might suggest that journalism has become more equal in terms of gender. However, upon closer inspection, I realised that things weren’t as progressive as they seemed. While men and women were both reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic, the topics assigned to journalists varied significantly with gender. I found that women were far more likely to cover stories on public health and the NHS than their male counterparts, whereas reporting of politics and economics was often carried out by men. This is consistent with previous work on women in journalism - ‘hard’ news stories relating to industry and politics tend to be given to men, while women are relegated to covering so-called ‘softer’ topics like health, social care and education. This is not true in every case, and I did record instances of women writing about politics and business. However, the general trends I observed speak to wider patriarchal norms in our society, wherein men are respected for technical expertise and intelligence, and women are valued in the realms of emotion, care and nurturing. A breakdown of the article topic by gender of the journalist is shown below [Figure 2].

[Figure 2]

I’d spent quite a while exploring what journalists had been reporting on when I suddenly thought to myself, “what about the topics which aren’t being written about?”. I’d combed through 121 news stories over a seven day period, but I hadn’t encountered anything about domestic violence or caring responsibilities. While these topics hadn’t come up, I’d read multiple articles about planning holidays around travel restrictions. It’s a well-known fact that domestic violence, for instance,

GUEST POST: Looking Deeper: Black and Minority Ethnic Women in the Scottish Parliament

Today we're publishing the next blog in a series from the current student placements Engender is hosting from the University of Strathclyde Applied Gender Studies and Research Methods course.

Today we're publishing the next blog in a series from the current student placements Engender is hosting from the University of Strathclyde Applied Gender Studies and Research Methods course.

Mary Galloway concludes her blog series in this third post, which focuses more deeply on the discussions of Black and minority ethnic women in the Scottish Parliament, and the importance of Parliament understanding the distinct ways that racialised and gendered oppression take shape for different communities. You can read Mary's first post here and second post here.

In this final blog, I will carry out a more focused analysis of the results produced by my research into the representation of women facing multiple discriminations in the Scottish Parliament. I have so far talked about 'women with multiple protected characteristics' quite abstractly. It is important to think about who these women actually are and why it matters that the multiplicity of their marginalisation is acknowledged. Black and minority ethnic (BME) women face both gendered and racial oppression, providing them with experiences that are distinct from white women and Black men. For example, Black and minority ethnic women were some of the worst affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. For this reason, it is crucial that the Scottish Parliament is attentive to the specific needs of this group.

In my search of the content of Scottish Parliamentary business during its 5th session, I used search terms of 'Black women', 'Asian women', 'women of colour', 'BME women' and 'Black and minority ethnic women'. The search term that produced the majority of results for this category of women was the latter term of Black and minority ethnic women. Though this term is importantly inclusive of the diverse ethnicities of women in Scotland, its domination in the results also displays a degree of homogenisation. The needs of Asian women and Black women are not necessarily symmetrical; for example, forced marriage and 'honour’-based violence are forms of abuse that particularly affect Asian women. Consequently, although Black and minority ethnic women all face racialised and gendered oppression, it is important that the distinct way that these take shape for different communities is discussed and understood in Parliament.

A number of BME women's issues were covered in the various areas of parliamentary business. For example, there was recognition of the disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 on Black and minority ethnic women and the prevalence of workplace harassment and discrimination against them. Upon comparing the content of the remarks made by MSPs versus witnesses in the Official Report, there was a notable difference. Witnesses' mentions of Black and minority ethnic women tended to be highly detailed and substantive, whereas MSPs' references tended to go no further than a nod to the difficulty of BME women's lives and calls for more diverse representation generally. MSPs' discussions of BME women were largely quite shallow despite the richness of witnesses' evidence. Furthermore, often when BME women were mentioned by MSPs, they were listed alongside a number of other marginalised women. For example, in a Meeting of the Parliament on International Women's Day 2020, Alison Johnstone of the Scottish Greens said that Parliament should tackle the harassment of women of colour, LBT (lesbian, bisexual, transgender) women, disabled women and refugee women in the workplace. Although this is a very important problem facing women with multiple protected characteristics worthy of discussion, it does not pay attention to the specific discrimination of BME women that is both racialised and gendered. This illustrates a lack of engagement with the fundamental notion that underpins intersectionality, whereupon the needs of communities with multiple protected characteristics are specific and in need of concentrated attention. It is consequently important for MSPs to make the most of the information provided to them by witnesses and their constituents about the reality of BME women's lives in order to affect change in their favour.

This focused look at the case of BME women has provided an insight into the details behind the numbers provided in previous blogs. Such an examination is vital as it uncovers not just how often women with multiple protected characteristics are being mentioned but what is actually being said in these instances. The discussion of Black and minority ethnic women must not be a tick-box exercise, and neither should the discussion of any women facing multiple discriminations.

GUEST POST: Who are the conversation starters in the Scottish Parliament when it comes to marginalised women?

Today we're publishing the next blog in a series from the current student placements Engender is hosting from the University of Strathclyde Applied Gender Studies and Research Methods course.

In Mary Galloway's second post, she builds on her research into how often multiply marginalised women are mentioned in the Scottish Parliament. Here, she looks more closely at who is starting these conversations and why this further calls for more diverse representation in Parliament. You can read Mary's first post here and third post here.

GUEST POST: Which women are visible in the Scottish Parliament?

Today we're publishing the next blog in a series from the current student placements Engender is hosting from the University of Strathclyde Applied Gender Studies and Research Methods course.

Following the local elections last week, it is clear that diverse representation is needed at all levels. Mary Galloway's research focuses on representation in the Scottish Parliament, and for her first post Mary maps out her research into the visibility of women with multiple marginalised identities, as well as discussing gender audits, and why an intersectional approach is needed in order to fully assess the representation and participation of all women in the Scottish Parliament. You can read Mary's second post here and third post here.

In February 2022, it was announced that the Scottish Parliament will undergo a gender audit, something for which Engender, along with other organisations and campaigns, has long advocated. This audit will assess the extent to which women participate in and are represented by the Scottish Parliament, following the guide created by the Inter-Parliamentary Union. While a great start towards a gender-sensitive Parliament, there are clear limitations in what an audit can do to bring an intersectional lens to women’s representation. It is crucial that to truly explore gender equality, we need to uncover the experiences and positions of all women in Holyrood, including those of the most marginalised. The project I am carrying out here aims to provide a snapshot of the representation of the women in Scotland whose lives are structured and limited not just by their gender but by their race, physical and mental abilities, and sexuality too.

Intersectionality is a concept brought forth primarily by Black feminists. It seeks to illuminate the way in which marginalised communities may have their experiences shaped by numerous structures of oppression simultaneously. For example, gendered oppression cannot wholly account for the discrimination faced by a disabled Black woman. Instead, her experience is shaped by racism, sexism and ableism all at once. What this research project seeks to highlight then, is that women with multiple protected characteristics have needs and concerns that are specific to their identity. An intersectional approach which pays attention to this multiplicity of the gendered experience is needed to fully assess the representation and participation of all women in the Scottish Parliament. The gender audit of the Scottish Parliament should proceed with an understanding and utilisation of intersectionality as far as it can within the limitations of auditing an overwhelmingly male, white institution.

Over the course of three blogs, I will delineate the findings of my research into the representation of women in the Scottish Parliament using an intersectional lens to exemplify the value of such an approach. This research has involved using the Scottish Parliament’s website and search tools, looking specifically at the Official Report, Written questions and answers, and Motions in Session 5 (May 2016 - May 2021). These search tools have enabled me to gather data, firstly on how often discussions about women with multiple protected characteristics were being had, secondly on who in Parliament was initiating these conversations, and thirdly on the substantive content of these discussions.

How often are marginalised women talked about?

The frequency of discussions about marginalised women separately from the broad category of ‘women’ provides a good indication of their visibility in the Scottish Parliament. It was found that, in all three areas of parliamentary business, the Official Report, Motions and Written questions and answers (WQAs), mentions of women with multiple protected characteristics were uncommon. Firstly, in the Official Report, search terms that listed a protected group alongside women, such as ‘disabled women’, yielded only 46 relevant results in total. To contextualise this, Session 5 was five years long and had 438 Meetings of the Parliament and 2204 committee meetings. Search terms that included women alongside another protected characteristic brought up only 51 motions out of 2717 (1.9%) in total and only 33 written questions and answers out of 33,334 questions (0.01%) in total. In relative terms, therefore, discussions of women that can be said to have had an intersectional approach in the Scottish Parliament were extremely rare. The presence of some references to women facing multiple discriminations indicates that there is an awareness of their need for focused attention separate from that of women in general. The concerns of multiply marginalised women are evidently being brought to the attention of people in parliament then; however, this has yet to translate into representation proportionate to their vulnerability.

Clearly, women facing multiple discriminations need greater representation in the Scottish Parliament; however, it is useful to look at where they are being discussed at present, who is initiating the conversations and what they are saying. The next blog in this series will do the former, uncovering whose participation in the Scottish Parliament is resulting in the discussion of marginalised women separately from women generally. The third blog will take a focused look at Black and minority ethnic women in order to exemplify the extent to which the specific needs of a community of vulnerable women are understood and represented by the Scottish Parliament.

GUEST POST: Precedented inequalities in unprecedented times

Here we've published the next in a series of blogs from the current student placements Engender is hosting from the University of Strathclyde Applied Gender Studies and Research Methods course.

In this post, Kirsty Rorrison discusses the COVID-19 pandemic, from it's impact on women and minoritised communities to it's representation in the media, and introduces research specifically focusing on how gender bias in political news reporting has operated during the pandemic. You can read Kirsty's second post here.

With the COVID-19 pandemic recently passing its two year anniversary, I’m sure many of us have been reflecting on the ways in which life has changed since the coronavirus first became a mainstream issue. We have all been impacted by the pandemic in one way or another - circumstances have changed personally, socially, politically and economically all across the world. However, while it may seem like everything in our society has fundamentally shifted, its underlying social structures have remained practically untouched. In fact, the COVID-19 pandemic can be seen as something of a magnifying glass for the oppressive social institutions forming the bedrock of modern society. In these "unprecedented times,” some things have reflected the precedent more than ever.

As a poem written at the height of the pandemic says, “we are in the same storm, but not in the same boat.” Far from being an equaliser, COVID-19 has instead emphasised the multitude of divisions within our society. For instance, those within ethnic minority groups were met with a much higher risk of infection and death from the virus than their white counterparts. Racism against people of East and Southeast Asian descent became particularly prominent in response to the hypothesised origins of the novel virus. Women have faced unique challenges balancing increased caring responsibilities with the rest of their lives, and were also put at risk by skyrocketing rates of domestic abuse during the pandemic. Low income children often struggled to access online learning, while wealthier pupils made the transition to remote education relatively easily. While we have all been living through a public health crisis, our situations have been very different; hardship has been discriminatory and disproportionate, often impacting those who were already struggling before COVID-19. The pandemic has been front page news for over two years now, and in a time where the public has relied so heavily on news reporting, and so much has been written about the pandemic, the oppressive structures which have compounded the hardships of COVID-19 were bound to be reflected in news coverage itself.

As a placement student with Engender, I have been given the opportunity to investigate the gendered dimensions of the pandemic, specifically in relation to its coverage in the media. COVID-19 has dominated the news cycle for the past two years, and this massive quantity of reporting offers extremely valuable insights into what life has been like during the pandemic. Work has already been undertaken which exposes biases in news coverage; for instance, it has been shown that reporting on the pandemic tends to over-represent the voices and interests of people who are white, middle class, and often male. I have been carrying out a content analysis on COVID-19 news coverage from some of Scotland’s most popular newspapers, hoping to understand how gender is manifested in reporting on the coronavirus. While I expect to encounter a huge amount of data regarding gender, media and COVID-19, I intend to primarily focus on the ways in which representations of politicians in the news have been gendered.

In these times of uncertainty, nations have turned to their political leaders for information, guidance and even comfort - news coverage reflects this increase in public attention received by politicians. Women in politics have always faced gender bias in media. Stereotypical gender roles and wider social structures inform the ways in which they are represented, scrutinised, and even obscured - this can be even more complicated for women who experience oppressions due to their race, sexuality, or other identities. Men and women in politics experience very different news reporting; this is especially obvious when their news coverage directly compared.

For my research project, I am exploring the following research questions:

- Are women in politics represented differently than men in politics in news reporting of the COVID-19 pandemic?

- If they are, how can this difference be contextualised in wider social structures?

It has already been established that the pandemic has amplified existing inequalities in Scotland. It has also been proven that women in politics faced gender bias in news coverage prior to the pandemic. I am hoping to find the convergence in these two facts by investigating how gender bias in political news reporting has functioned during the COVID-19 pandemic. In other words, I will be considering how the precedent of gender bias in political news reporting has persisted despite these unprecedented times. My next two blog posts will detail my findings and consider the implications of the data this project produces. For now, I ask what the magnifying glass of COVID-19 may reveal about politics, gender and media.

Downloads

Engender Briefing: Pension Credit Entitlement Changes

From 15 May 2019, new changes will be introduced which will require couples where one partner has reached state pension age and one has not (‘mixed age couples’) to claim universal credit (UC) instead of Pension Credit.

Engender Briefing: Pension Credit Entitlement Changes

From 15 May 2019, new changes will be introduced which will require couples where one partner has reached state pension age and one has not (‘mixed age couples’) to claim universal credit (UC) instead of Pension Credit.

Engender Parliamentary Briefing: Condemnation of Misogyny, Racism, Harassment and Sexism

Engender welcomes this Scottish Parliament Debate on Condemnation of Misogyny, Racism, Harassment and Sexism and the opportunity to raise awareness of the ways in which women in Scotland’s inequality contributes to gender-based violence.

Engender Parliamentary Briefing: Condemnation of Misogyny, Racism, Harassment and Sexism

Engender welcomes this Scottish Parliament Debate on Condemnation of Misogyny, Racism, Harassment and Sexism and the opportunity to raise awareness of the ways in which women in Scotland’s inequality contributes to gender-based violence.

Gender Matters in Social Security: Individual Payments of Universal Credit

A paper calling on the Scottish Government to automatically split payments of Universal Credit between couples, once this power is devolved to the Scottish Parliament.

Gender Matters in Social Security: Individual Payments of Universal Credit

A paper calling on the Scottish Government to automatically split payments of Universal Credit between couples, once this power is devolved to the Scottish Parliament.

Gender Matters Manifesto: Twenty for 2016

This manifesto sets out measures that, with political will, can be taken over the next parliamentary term in pursuit of these goals.

Gender Matters Manifesto: Twenty for 2016

This manifesto sets out measures that, with political will, can be taken over the next parliamentary term in pursuit of these goals.

Scottish NGO Briefing for UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women

Joint briefing paper for the UN Rapporteur on Violence Against Women.

Scottish NGO Briefing for UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women

Joint briefing paper for the UN Rapporteur on Violence Against Women.

Newsletter

Sign up to receive our newsletter here:

Sign up to our mailing list

Receive key feminist updates direct to your inbox:

![Bright pink graphic that reads: "Stereotypical gender roles and wider social structures inform the ways in which they [women] are represented, scrutinised, and even obscured - this can be even more complicated for women who experience oppressions due to their race, sexuality, or other identities."](/siteimages/Blog/resized/student-blog-kirsty-2022-1080x1080-400.png)