Engender blog

The ‘family cap’ and ‘rape clause’: where do we go from here?

Sometimes in the life of a gender advocate the stars align to create a Platonic policy process. A proposal comes forward from government that is simple and easy to understand. Gender-disaggregated data is available. Other women’s organisations have the resource and interest to engage in a discussion about how to respond. Women are easy to include in the conversation. Feminist analysis leads inexorably to specific policy calls. Colleagues from across civil society agree with our take on the government’s proposals, and integrate our asks into their lobbying strategies. Government listens keenly to our input and develops its policy accordingly.

Most of the time, though, there is much more friction in feminist policy and advocacy. Government proposals may be vague or unclear, or broken into chunks that are hard to knit together. Consultation processes may be too short. There may be no data on how the policy will affect women and men, or no data at all. Other women’s organisations may not have the time or resource to focus on a specific area of policy, because of competing priorities. Feminist analysis may produce politically untenable asks. Other women’s organisations may disagree on our analysis or approach, or have other political drivers to sit out a particular issue. Colleagues from across civil society may feel that the gender dimension is a distraction or dilution of their own urgent priorities. Government may intentionally shape a consultation process to distance civil society, and women’s organisations.

The recent lobby and advocacy around the ‘family cap’ and ‘rape clause’ has definitely involved some friction. What that is, and why that has been sheds some light on broader questions about gender and policy.

There are lots of people in Scotland who have only become aware of the ‘rape clause’ in the last few weeks. In fact, its story began almost two years ago. So what’s been going on, and where do we go from here?

First things first: what is the ‘family cap’?

The ‘family cap’ is a legislative measure that limits payments of child tax credits and will limit the child element of the single new UK social security payment, Universal Credit. The rollout of Universal Credit is years behind schedule but the cap will eventually limit elements related to the number of children a family has, like the housing element. Child tax credits, it’s worth reminding ourselves, are for people who are in paid work. They are a state subsidy intended to fill the gap between low wages and the income levels households require to buy the things they need.

The thinking behind ‘family caps’ is flawed. It links the idea of having children with families doing hard-headed sums about income levels. It imagines that poorer families should just be more ‘responsible’ about the number of children they have. At its heart, it's an intrusion into women's freedom to make reproductive choices that suit them. Of course, life isn’t neat and predictable. People from some faiths make a religious decision to avoid or limit contraceptive use. Bereavement, relationship breakdown, contraceptive failure, and new relationships that blend families aren’t necessarily our plans at the start of life, but will inevitably happen to hundreds of thousands of people.

The unpredictability of life means that ‘family caps’ don’t work. Many decades after caps were introduced in the United States, they have failed on their own terms by not reducing the number of children of social security recipients. What they have done is pushed families into deeper poverty. Many women in states in which ‘family caps’ operate are unable to buy nappies or food for their children, and live in inadequate housing.

But what does that have to do with the ‘rape clause’?

When the Tories formed the UK Government in 2015 they did so on a manifesto that promised cuts to social security. In the summer budget of the same year the ‘family cap’ was introduced, and the ‘rape clause’ was sketched out.

The ‘rape clause’ provides an exemption to the two-child limit where pregnancies have resulted from rape. This notion horrified gender advocates when they initially read about it in the summer budget. Firstly, it clarified the thinking that sat at the back of the ‘family cap’. This framed the birth of third and subsequent children in low-wage families as the product of women’s irresponsibility, with exemptions for unforeseeable children. It implicitly suggests that child poverty is acceptable if low-wage women have more than two children. Secondly, and importantly for violence against women organisations, there seemed no way in which a state could gather information about rape from women that would not retraumatise women, or breach women’s and children’s right to privacy.

So then the ‘family cap’ and ‘rape clause’ became law?

Not all at the same time.

The UK Government moved quickly in the first half of 2015 on a large piece of social security legislation that put the ‘family cap’ in place. The Welfare Reform and Work Bill progressed through the Houses of Parliament at a substantial clip, in parallel with a UK Labour leadership election. Although civil society organisations briefed on the substantial impact on child poverty and women’s poverty of the proposed changes, the content of the bill was locked down relatively early on in the year. Despite valiant analytical efforts by the Women’s Budget Group and others, nothing but the broadest outline of the women’s equality and rights dimensions cut through to the general public.

In Scotland, women’s organisations came together to review the disastrous impact the changes in UK social security policy were likely to have on women and women’s equality. Working together, we tracked the transfer of new social security powers to Scotland and issued calls for action by Scottish Government in the use of these powers.

One piece of work that the Welfare Reform and Work Act left unfinished was the detail of the exemptions. The ‘rape clause’ that had been floated in the summer budget of 2015 was not part of the Act. Instead, it created space for exemptions to be created by secondary legislation. (Secondary legislation is generally used for bits of law that aren’t contentious, but include a lot of detail that parliamentarians don’t want to burn time on.)

With no consultation forthcoming the ‘rape clause’ was pushed on to the back burner by women’s organisations. Alison Thewliss MP raised questions about the ‘rape clause’ 25 times in the House, and received little in the way of clarifying detail in response. Coverage in Scotland of her attempts, particularly by new media, began to sensitise activists to concerns about the clause.

On the Friday after the US Presidential election, the DWP sent an email at 5pm announcing a month-long consultation on the ‘rape clause’ and other exemptions. Despite admonitions that the consultation was solely about implementation and not about the 'family cap', Engender responded with our views on the broader two-child limit as well as on the ways in which we believe the ‘rape clause’ to be a breach of women’s rights.

The DWP was unmoved by our analysis, and two statutory instruments were created that slipped onto the statute books in March 2017. This used a so-called 'negative procedure' that meant no parliamentary scrutiny was possible. At this point, alarm was building within women’s organisations about what the specifics of the rape clause might mean for women. Although the question of the ‘family cap’ had been put to bed, parliamentarily, the ‘rape clause’ itself was still a live concern. Detailed conversations with DWP, Treasury, and HMRC suggested a failure to consider the most basic questions about implementation, including features that presented a risk to women’s lives and to rape and domestic abuse prosecutions. DWP declined to provide an equality impact assessment of the policy.

With parliamentary and policymaking avenues closing before us, Engender, Rape Crisis Scotland, and Scottish Women’s Aid engaged with the Secondary Legislation Scrutiny Committee of the House of Lords. (This Committee is the only one empowered to refer secondary legislation back to the House.) Although they produced a report that characterised the clause as ‘unworkable’ it is now up to individual Lords to decide how they wish to respond to this assessment.

With no debate having ever taken place on the serious failures in the design and concept of the ‘rape clause’ itself, and limited scope for reopening the contents of Welfare Reform and Work Act, our organisations took the view that petitioning the Petitions Committee of the UK Parliament would secure a helpful debate. This petition will now fall when Parliament is dissolved for the general election (read our joint statement here).

So if the ‘family cap’ is the real problem, then why has the ‘rape clause’ got so much attention?

The Welfare Reform and Work Bill was fast out of the parliamentary traps after the new UK Government was formed in 2015. The ‘family cap’ was folded into an enormous set of changes being made to social security. The dizzying level of detail and sweep of changes meant that reporting tended to cover the broad thrust of reforms. With social security hard to summarise, and very few gender and social security experts on the commentariat circuit, lots of detail ended up under the rug.

In terms of attracting public and policy attention the 'rape clause' had several advantages. It stood alone, in that the exemptions were being outlined almost two years after the initial bill content was finalised. It also sounds immediately troubling to people, and is relatively straightforward to summarise. So while focus on the 'rape clause' is understandable, it's vital that we understand the 'family cap' policy that underpins it.

So what’s next?

Engender will be lobbying political parties to include a rethink on the ‘family cap’ and social security in their UK parliament manifestos for the snap General Election in June. The Equality and Human Rights Commission has written to the UK Government Minister responsible for social security to discuss the breaches to equality and rights that they believe the ‘family cap’ will effect. Organisations across Scotland and the UK are considering a legal challenge, although that will be very complicated. There are still no third-party referrers for the ‘rape clause’ in Scotland, as far as we know. We will be discussing with Scottish Government as they take forward their own social security bill how they might put women’s equality and rights at the heart of their own legislative and policymaking agenda.

Share this post on …

Comments: 0 (Add)

Downloads

Engender Response to UK Government Consultation on Exceptions to the Reforms Which Limit the Child Elements in Child Tax Credit and Universal Credit to a Maximum of Two Children

Engender fundamentally rejects the principles behind both reducing vital social security for mothers of more than two children, and making an exception where a child is conceived as a result of rape.

Engender Response to UK Government Consultation on Exceptions to the Reforms Which Limit the Child Elements in Child Tax Credit and Universal Credit to a Maximum of Two Children

Engender fundamentally rejects the principles behind both reducing vital social security for mothers of more than two children, and making an exception where a child is conceived as a result of rape.

Engender Submission to the Scottish Parliament Social Security Committee Call for Evidence on the Two-child Limit for Tax Credits and Universal Credit

Engender welcomes the opportunity to present evidence to the Social Security Committee on the two-child limit.

Engender Submission to the Scottish Parliament Social Security Committee Call for Evidence on the Two-child Limit for Tax Credits and Universal Credit

Engender welcomes the opportunity to present evidence to the Social Security Committee on the two-child limit.

Engender Submission to the Scottish Parliament Social Security Committee on the Social Security (Scotland) Bill

Engender welcomes the opportunity to respond to the Committee’s call for views.

Engender Submission to the Scottish Parliament Social Security Committee on the Social Security (Scotland) Bill

Engender welcomes the opportunity to respond to the Committee’s call for views.

Joint Response to the UK Government Work and Pensions Committee Short Inquiry into the Impact of the Universal Credit Household Payment

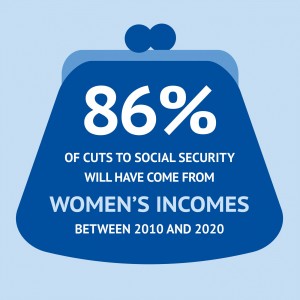

Since 2010, the UK Government has pursued an austerity agenda and programme of ‘welfare reform’ which will result in a total of £82 billion of cuts to the social security budget by 2020.

Joint Response to the UK Government Work and Pensions Committee Short Inquiry into the Impact of the Universal Credit Household Payment

Since 2010, the UK Government has pursued an austerity agenda and programme of ‘welfare reform’ which will result in a total of £82 billion of cuts to the social security budget by 2020.

Newsletter

Sign up to receive our newsletter here:

Sign up to our mailing list

Receive key feminist updates direct to your inbox: