Engender blog

Guest Blog: Gender and precarity in the 21st century workplace – universities and beyond

Even before the pandemic, women’s employment was increasingly precarious. Work from our sisters at Close the Gap shows that women are more likely to be in insecure work, on zero hours or temporary contracts, and are two-thirds of workers earning less than the real living wage. Black and minoritised women are overrepresented in precarious work, and are more likely to be on zero hours contracts.

Today on our blog, researchers Dr Lena Wånggren and Dr Cécile Ménard share their work on the gendered impact of job insecurity and precarity, and why we need to make women’s unpaid, unrecognised work visible. Illustrations throughout are by Maria Stoian.

Casualisation – the precarisation of work, in which core business previously done by colleagues in permanent jobs is done on an hourly, fixed-term, sessional, and one-off basis – is a key feature of the 21st-century workplace.

This blog post, written by two long-term insecurely employed feminist researchers at a Scottish university, shares research on job insecurity and inequalities in the UK workplace. Making visible women’s unpaid and invisibilised work and the intersectionally gendered impacts of job insecurity, we highlight what needs to change.

The gendered impact of job security

Job insecurity has become the norm in UK workplaces, especially since the 2008 financial crisis and the austerity measures that followed, when anti-feminist cuts to social infrastructure went hand in hand with anti-worker legislation and policies across sectors. UK Universities, once seen as a prestigious place of privilege, are one of the most casualised (that is to say, reliant on insecure contracts) sectors in the UK: around half of academic staff are employed on insecure contracts, and higher education is the second most casualised sector in the UK after hospitality.

Precarity is not experienced equally. Migrants and racially minoritised persons are more likely to be employed on insecure contracts and, in fact, more likely to be in severely insecure work. While trade unions, feminist researchers and campaign groups have highlighted the detrimental and intersectionally gendered impact of job insecurity, including the exacerbated risk of sexual and racial violence, there is a lack of action among employers and governments to tackle the problem. To address the equalities impact of contractual precarity, we need an intersectional feminist perspective with a focus on workplace justice.

Job security is a workplace issue and a gender equality issue

There are two ways in which we approach gender and precarity in the workplace: from an intersectional feminist framing and from the issue of workplace justice. In the context of our 21st-century precarisation of work across sectors, with gig economy and platform models spreading, and the gendered and intersectional impacts of such an economy, specific problems need tackling. One specific and urgent issue is the financial instability of women in precarious work, with dependency on a partner related to risks of gender-based violence, especially for groups of migrant women who have no recourse to public funds. Family planning is affected when a stable job or living situation is not on the horizon. Job security is both a workplace issue and a gender equality issue.

The university sector – still seen by many as a prestigious place of privilege – reproduces the same structural inequalities as the broader society. More than 40% of teaching staff are on hourly or zero-hour contracts that often do not pay enough to live on, with some relying on food banks to get by. While hourly workers are underpaid for the amount of work they are contracted to do, and the work is insecure, researchers are usually on fixed-term contracts, and are encouraged to apply for prestigious awards and grants for their careers in their own time. If they are successful, there is no guarantee of job security; the prestige and cashflow benefit the institution while the worker remains expendable.

The university sector – still seen by many as a prestigious place of privilege – reproduces the same structural inequalities as the broader society. More than 40% of teaching staff are on hourly or zero-hour contracts that often do not pay enough to live on, with some relying on food banks to get by. While hourly workers are underpaid for the amount of work they are contracted to do, and the work is insecure, researchers are usually on fixed-term contracts, and are encouraged to apply for prestigious awards and grants for their careers in their own time. If they are successful, there is no guarantee of job security; the prestige and cashflow benefit the institution while the worker remains expendable.

Women’s unpaid work in universities and beyond

In our current research project, In Their Own Time, we have partnered with our trade union, UCU, to examine a key problem in struggles for gender equality: the undervaluing of women’s work. Unpaid labour has long been at the heart of the feminist struggle. From the Wages for Housework campaign to the work of scholars such as Selma James, Dorothy Smith and Patricia Hill Collins, feminists have shown that defining ‘work’ only as paid labour renders invisible the gendered, racialised labour that keeps institutions—and societies—going. While reproductive work, such as care work, is gendered and racialised, women’s work across society is also underpaid, undervalued, and invisibilised, with the labour market maintaining sexist, racist and ableist structures. This gendered undervaluing of work shows through in expectations of unpaid work and lack of support structures in the academic workplace.

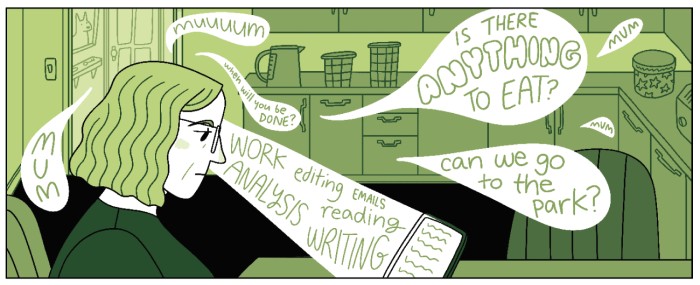

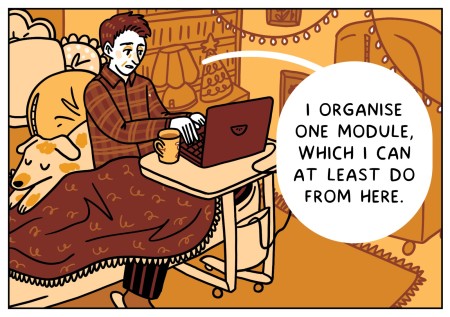

Working with the fantastic feminist illustrator Maria Stoian, the participants in the project tell stories of combining paid and unpaid work, visa applications, health issues, and a range of insecure jobs. Steph, a single mum who juggles housework, childcare, and two insecure jobs, states: ‘Every year I panic – am I going to have a job this year?’ What she calls her ‘own time’ is at night when she does emails for her jobs after her child has gone to bed. Susie, a casualised researcher for 20 years, remarks on the expectation of working unpaid in academia, for example, applying for funding in her own time even when not paid for it: non-academic colleagues think ‘it’s crazy’, but in academia, it’s normalised. She highlights that not everyone can work for free – with childcare responsibilities, she needs flexibility. Alex is a disabled academic whose disability has been made worse by precarity. Another participant, Eimhir, explains that she spends managing her chronic health condition alongside paid work and cannot fit in further unpaid academic work even if this is required to succeed in the university. Olivia, a mum and researcher, keeps her work with her all the time – including marking dissertations by the pool when the kids are at swimming lessons on Saturday morning. Meanwhile, Gwen is a trans academic in precarious part-time jobs: she gives lectures, does research, organises events, and supports her colleagues, all unpaid in her spare time.

Working with the fantastic feminist illustrator Maria Stoian, the participants in the project tell stories of combining paid and unpaid work, visa applications, health issues, and a range of insecure jobs. Steph, a single mum who juggles housework, childcare, and two insecure jobs, states: ‘Every year I panic – am I going to have a job this year?’ What she calls her ‘own time’ is at night when she does emails for her jobs after her child has gone to bed. Susie, a casualised researcher for 20 years, remarks on the expectation of working unpaid in academia, for example, applying for funding in her own time even when not paid for it: non-academic colleagues think ‘it’s crazy’, but in academia, it’s normalised. She highlights that not everyone can work for free – with childcare responsibilities, she needs flexibility. Alex is a disabled academic whose disability has been made worse by precarity. Another participant, Eimhir, explains that she spends managing her chronic health condition alongside paid work and cannot fit in further unpaid academic work even if this is required to succeed in the university. Olivia, a mum and researcher, keeps her work with her all the time – including marking dissertations by the pool when the kids are at swimming lessons on Saturday morning. Meanwhile, Gwen is a trans academic in precarious part-time jobs: she gives lectures, does research, organises events, and supports her colleagues, all unpaid in her spare time.

As seen in our project, the reliance on intersectionally gendered unpaid labour creates further inequalities because it excludes those whose own time is other people’s time – such as those with caring responsibilities, the majority of whom remain women – or those whose own time is recovery time, as is the case for many disabled individuals.

Job security now!

Precarity is everywhere: environmental, geopolitical, and at work. We can make distinct policy changes to address this: we need decent, secure jobs for women and for all - that is key to gender equality. Together with trade unions, workers’ organisations, and feminist organisations, we call for immediate institutional and governmental action on job insecurity, intersectional gender inequality, and an end to the invisibilisation of women’s work. Addressing job insecurity requires more than reforming individual contracts—it demands dismantling the structures that normalise insecure, unpaid labour as inevitable. Such action extends far beyond universities. Across sectors, a renewed feminist politics of labour is urgently needed—one that centres care, builds intersectional solidarity and challenges the exploitation of those whose time has always been devalued.

This project was supported by the UKRI and the British Academy Funding through the Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Caucus (ES/X008444/1)

Recommended viewing: Our Time Is Coming Now (BBC, Selma James & Michael Rabiger, 1970)

Guest posts do not necessarily reflect the views of Engender, and all language used is the author’s own. Bloggers may have received some editorial support from Engender, and may have received a fee from our commissioning pot. We aim for our blog to reflect a range of feminist viewpoints, and offer a commissioning pot to ensure that women do not have to offer their time or words for free.

Interested in writing for the Engender blog? Find out more here.

Share this post on …

Comments: 0 (Add)

Sign up to our mailing list

Receive key feminist updates direct to your inbox: