Engender blog

Engender statement on the weaponisation of violence against women and girls

-450.png) We are increasingly alarmed at the way women’s rights and safety are being weaponised to demonise minorities across the UK. This kind of distortion of the facts only causes harm to individuals and communities and does nothing to end violence against women and girls.

We are increasingly alarmed at the way women’s rights and safety are being weaponised to demonise minorities across the UK. This kind of distortion of the facts only causes harm to individuals and communities and does nothing to end violence against women and girls.

As Engender, we want to add our voice to calls for action against the spread of hate and misinformation, and for protection and safe and legal routes to be provided for people fleeing war and crisis to the UK. We also want to express our solidarity with racialised and other minority communities who are being made to feel unsafe by hate speech, incitement of violence and far-right protests, including here in Scotland.

Men’s violence against women and girls is endemic in our society and is caused by gender inequality. Spreading inaccurate and hateful rhetoric only generates more violence and creates a distraction from the political commitments that are needed to address it. Improvements to our social security system, investment in childcare, social care, education, housing and community resources, are the things that make a real difference to women.

The false and racist narratives these groups are promoting ignore the fact that violence against women and girls is most commonly perpetrated by someone close to the victim. Last year, the UN reported that the home is the most dangerous place for women, with 60% of women killed by men globally in 2023 dying at the hands of a partner or family member. Two out of every five people arrested during far-right riots in summer 2024 had previously been reported to the police for domestic abuse.

Racism, Islamophobia and anti-migrant attitudes play a major role in the increased risk of violence that women of colour, asylum-seeking and refugee women face.

The UK’s asylum and immigration systems compound this harm, particularly through the brutal No Recourse to Public Funds (NRPF) condition, which increases women’s risk of gender-based violence and restricts access to support, including refuge accommodation.

Invitation to Tender: Equal Representation 2025/26 Candidate Research.

-750.png)

Engender’s Equal Representation in Politics Project aims to help create a Scotland where there is sustainable equal representation of women in all their diversity in politics, ensuring women’s perspectives shape decision-making, reducing gender inequality, and creating better outcomes for women and society.

The project seeks to create change by encouraging all those who hold power to shape the political landscape, including political parties, councils, government, and parliament, to take action to increase the representation of women and improve levels of diversity among women’s representation.

We are seeking a consultant:

- To review and collate a list of women MSPs who have publicly stated that they intend to stand down before the Holyrood 2026 elections.

- To review and collate the reasons given publicly by these MSPs for reaching the decision to stand down.

- To compile a list of candidates for each major party for the Holyrood 2021, broken down by protected characteristic where possible.

- To compile a list of candidates for each major party for the Holyrood 2026, broken down by protected characteristic where possible.

- To create and circulate a survey, and analyse and collate findings, of all women MSPs standing down on the factors that influenced their decision.

The deadline for tenders to be submitted is 5pm, Monday 15th September.

Please find all the details and how to apply, here.

Guest Blog: Gender and precarity in the 21st century workplace – universities and beyond

Even before the pandemic, women’s employment was increasingly precarious. Work from our sisters at Close the Gap shows that women are more likely to be in insecure work, on zero hours or temporary contracts, and are two-thirds of workers earning less than the real living wage. Black and minoritised women are overrepresented in precarious work, and are more likely to be on zero hours contracts.

Today on our blog, researchers Dr Lena Wånggren and Dr Cécile Ménard share their work on the gendered impact of job insecurity and precarity, and why we need to make women’s unpaid, unrecognised work visible. Illustrations throughout are by Maria Stoian.

Casualisation – the precarisation of work, in which core business previously done by colleagues in permanent jobs is done on an hourly, fixed-term, sessional, and one-off basis – is a key feature of the 21st-century workplace.

This blog post, written by two long-term insecurely employed feminist researchers at a Scottish university, shares research on job insecurity and inequalities in the UK workplace. Making visible women’s unpaid and invisibilised work and the intersectionally gendered impacts of job insecurity, we highlight what needs to change.

The gendered impact of job security

Job insecurity has become the norm in UK workplaces, especially since the 2008 financial crisis and the austerity measures that followed, when anti-feminist cuts to social infrastructure went hand in hand with anti-worker legislation and policies across sectors. UK Universities, once seen as a prestigious place of privilege, are one of the most casualised (that is to say, reliant on insecure contracts) sectors in the UK: around half of academic staff are employed on insecure contracts, and higher education is the second most casualised sector in the UK after hospitality.

Precarity is not experienced equally. Migrants and racially minoritised persons are more likely to be employed on insecure contracts and, in fact, more likely to be in severely insecure work. While trade unions, feminist researchers and campaign groups have highlighted the detrimental and intersectionally gendered impact of job insecurity, including the exacerbated risk of sexual and racial violence, there is a lack of action among employers and governments to tackle the problem. To address the equalities impact of contractual precarity, we need an intersectional feminist perspective with a focus on workplace justice.

Job security is a workplace issue and a gender equality issue

There are two ways in which we approach gender and precarity in the workplace: from an intersectional feminist framing and from the issue of workplace justice. In the context of our 21st-century precarisation of work across sectors, with gig economy and platform models spreading, and the gendered and intersectional impacts of such an economy, specific problems need tackling. One specific and urgent issue is the financial instability of women in precarious work, with dependency on a partner related to risks of gender-based violence, especially for groups of migrant women who have no recourse to public funds. Family planning is affected when a stable job or living situation is not on the horizon. Job security is both a workplace issue and a gender equality issue.

The university sector – still seen by many as a prestigious place of privilege – reproduces the same structural inequalities as the broader society. More than 40% of teaching staff are on hourly or zero-hour contracts that often do not pay enough to live on, with some relying on food banks to get by. While hourly workers are underpaid for the amount of work they are contracted to do, and the work is insecure, researchers are usually on fixed-term contracts, and are encouraged to apply for prestigious awards and grants for their careers in their own time. If they are successful, there is no guarantee of job security; the prestige and cashflow benefit the institution while the worker remains expendable.

The university sector – still seen by many as a prestigious place of privilege – reproduces the same structural inequalities as the broader society. More than 40% of teaching staff are on hourly or zero-hour contracts that often do not pay enough to live on, with some relying on food banks to get by. While hourly workers are underpaid for the amount of work they are contracted to do, and the work is insecure, researchers are usually on fixed-term contracts, and are encouraged to apply for prestigious awards and grants for their careers in their own time. If they are successful, there is no guarantee of job security; the prestige and cashflow benefit the institution while the worker remains expendable.

Women’s unpaid work in universities and beyond

In our current research project, In Their Own Time, we have partnered with our trade union, UCU, to examine a key problem in struggles for gender equality: the undervaluing of women’s work. Unpaid labour has long been at the heart of the feminist struggle. From the Wages for Housework campaign to the work of scholars such as Selma James, Dorothy Smith and Patricia Hill Collins, feminists have shown that defining ‘work’ only as paid labour renders invisible the gendered, racialised labour that keeps institutions—and societies—going. While reproductive work, such as care work, is gendered and racialised, women’s work across society is also underpaid, undervalued, and invisibilised, with the labour market maintaining sexist, racist and ableist structures. This gendered undervaluing of work shows through in expectations of unpaid work and lack of support structures in the academic workplace.

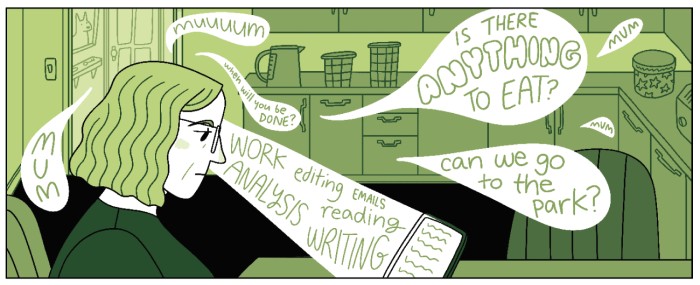

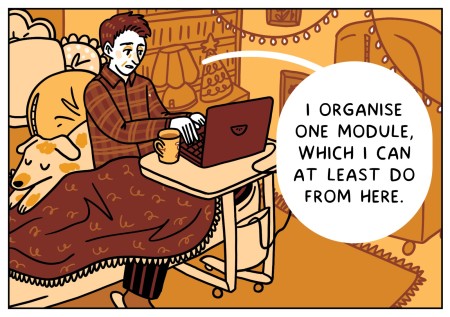

Working with the fantastic feminist illustrator Maria Stoian, the participants in the project tell stories of combining paid and unpaid work, visa applications, health issues, and a range of insecure jobs. Steph, a single mum who juggles housework, childcare, and two insecure jobs, states: ‘Every year I panic – am I going to have a job this year?’ What she calls her ‘own time’ is at night when she does emails for her jobs after her child has gone to bed. Susie, a casualised researcher for 20 years, remarks on the expectation of working unpaid in academia, for example, applying for funding in her own time even when not paid for it: non-academic colleagues think ‘it’s crazy’, but in academia, it’s normalised. She highlights that not everyone can work for free – with childcare responsibilities, she needs flexibility. Alex is a disabled academic whose disability has been made worse by precarity. Another participant, Eimhir, explains that she spends managing her chronic health condition alongside paid work and cannot fit in further unpaid academic work even if this is required to succeed in the university. Olivia, a mum and researcher, keeps her work with her all the time – including marking dissertations by the pool when the kids are at swimming lessons on Saturday morning. Meanwhile, Gwen is a trans academic in precarious part-time jobs: she gives lectures, does research, organises events, and supports her colleagues, all unpaid in her spare time.

Working with the fantastic feminist illustrator Maria Stoian, the participants in the project tell stories of combining paid and unpaid work, visa applications, health issues, and a range of insecure jobs. Steph, a single mum who juggles housework, childcare, and two insecure jobs, states: ‘Every year I panic – am I going to have a job this year?’ What she calls her ‘own time’ is at night when she does emails for her jobs after her child has gone to bed. Susie, a casualised researcher for 20 years, remarks on the expectation of working unpaid in academia, for example, applying for funding in her own time even when not paid for it: non-academic colleagues think ‘it’s crazy’, but in academia, it’s normalised. She highlights that not everyone can work for free – with childcare responsibilities, she needs flexibility. Alex is a disabled academic whose disability has been made worse by precarity. Another participant, Eimhir, explains that she spends managing her chronic health condition alongside paid work and cannot fit in further unpaid academic work even if this is required to succeed in the university. Olivia, a mum and researcher, keeps her work with her all the time – including marking dissertations by the pool when the kids are at swimming lessons on Saturday morning. Meanwhile, Gwen is a trans academic in precarious part-time jobs: she gives lectures, does research, organises events, and supports her colleagues, all unpaid in her spare time.

As seen in our project, the reliance on intersectionally gendered unpaid labour creates further inequalities because it excludes those whose own time is other people’s time – such as those with caring responsibilities, the majority of whom remain women – or those whose own time is recovery time, as is the case for many disabled individuals.

Job security now!

Precarity is everywhere: environmental, geopolitical, and at work. We can make distinct policy changes to address this: we need decent, secure jobs for women and for all - that is key to gender equality. Together with trade unions, workers’ organisations, and feminist organisations, we call for immediate institutional and governmental action on job insecurity, intersectional gender inequality, and an end to the invisibilisation of women’s work. Addressing job insecurity requires more than reforming individual contracts—it demands dismantling the structures that normalise insecure, unpaid labour as inevitable. Such action extends far beyond universities. Across sectors, a renewed feminist politics of labour is urgently needed—one that centres care, builds intersectional solidarity and challenges the exploitation of those whose time has always been devalued.

This project was supported by the UKRI and the British Academy Funding through the Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Caucus (ES/X008444/1)

Recommended viewing: Our Time Is Coming Now (BBC, Selma James & Michael Rabiger, 1970)

Guest posts do not necessarily reflect the views of Engender, and all language used is the author’s own. Bloggers may have received some editorial support from Engender, and may have received a fee from our commissioning pot. We aim for our blog to reflect a range of feminist viewpoints, and offer a commissioning pot to ensure that women do not have to offer their time or words for free.

Interested in writing for the Engender blog? Find out more here.

Guest Blog: Why do older women in Scotland experience further financial inequality?

Women experience high levels of pension inequality, due to women’s care responsibilities, part-time work, occupational segregation, the gender pay gap and maternity and gender discrimination at work, reducing women’s access to both state and private pensions. In this guest blog, Louise Brady from Independent Age explores the links between state pensions and gender inequality, what we can learn from the Older People’s Economic Wellbeing Index, and what needs to change.

The income gap that exists for women in Scotland during their working lives doesn’t end when they reach State Pension age. It persists - with lower wages, inadequate social security payments and time out of the recognised labour force due to caring responsibilities all negatively impacting savings, pensions and overall finances as women grow older.

It’s unacceptable that 96,782 pension-aged women in Scotland today live in poverty, with many more living just above this threshold.

The UK State Pension and gender inequality

The UK State Pension and gender inequality

The full amount of the UK’s new State Pension (paid to those who turned State Pension age after 2016) in the last financial year was just over £11,500 or £221.20 per week. On average, the weekly amount of new State Pension received by women in Scotland last August was around £5 less than men (£211.22 compared to £216.30), and £10 less per week than the maximum amount (or £520 less annually).

To get the maximum weekly payment amount, older people need to have paid 35 years of National Insurance contributions based on full-time work. According to the latest Scotland Census, women who are currently working are almost 4 times more likely than men to be in part-time jobs. Going by current rules, many of these women will receive less than the maximum amount of the new State Pension when they reach pensionable age.

However, it’s important to note that most older people (63%) in Scotland, including 70% of women, receive the pre-2016 State Pension instead (often referred to as the ‘old’ State Pension). The maximum amount for this is even lower – for financial year 2024/25 it was £169.50 per week or £8,814 a year.

While the rules and detail for the old State Pension are complex, the gendered income gap here is clear. The latest available data shows that last August only 77% of women in Scotland on the old State Pension received the full weekly amount, compared to 97% of men.

The Older People’s Economic Wellbeing Index: Scotland 24-25

The Older People’s Economic Wellbeing Index: Scotland 24-25

When looking at the drivers of poverty among older women in Scotland, the income gap that extends from working age to pension age is central. At Independent Age we recently published research which found that 68% of women in Scotland receive a pension from a former employer, compared to 75% of men. And while 26% of men receive income from a personal pension, this falls to 17% of women.

Our research can be found in the Older People’s Economic Wellbeing Index: Scotland, 2024-25, the first of an annual series of nationally representative polling of people aged 66 and over in Scotland, designed to gain a further understanding of the financial wellbeing and lives of older people.

The Index highlights the experiences of pensioners in Scotland who are more likely to live in poverty, including people with caring responsibilities, people who have a disability or health condition, renters, and unsurprisingly, women.

Shockingly, one quarter (24%) of older women reported having an income of less than £15,000. This is compared to 13% of men.

Older people were asked about the actions they’d taken as a result of financial difficulties, with the results revealing that women more likely than men to report that they occasionally skipped meals (13%; 9%), at least occasionally reduce the quality of their food (28%; 22%), frequently or always cut back on heating or utilities (23%; 17%), and frequently or always reduce their social interactions (14%; 11%).

The poll also looked at the experiences of one-person pensioner households, a group which is disproportionally made up of women (about 70%). Official statistics show that 22% (one in five) women above the State Pension age who live alone also live in poverty, compared to 16% (one in seven) of one-person male pensioner households.

What needs to change

The results from our first Older People’s Economic Wellbeing Index: Scotland provide further evidence on the persistence and impact of the gendered income gap for older women. For next year’s edition of the Older People’s Economic Wellbeing Index to show improvements across all areas, urgent action is needed.

The Scottish Government should introduce a strategy to tackle pensioner poverty by using devolved powers as far as possible. The UK Government needs to ensure that reserved social security entitlements, including the State Pension and Pension Credit, are set at an adequate level.

Policy makers across both Parliaments need to consider the reasons why some pensioners are more likely to live in poverty than others. Addressing the inequalities women face during their working age lives, and ensuring the social security system is adequate and affords a decent standard of life is central to reducing pensioner poverty, and the disproportionate impact of it that is experienced by women.

You can read the first Older People’s Economic Wellbeing Index from Independent Age here.

If you’re over State Pension age and struggling financially, you can find information from Independent Age on their website or you can call their Helpline on 0800 319 6789. To hear more about Independent Age’s policy and public affairs work in Scotland, please contact Scotlandpublicaffairs@independentage.org.

Guest posts do not necessarily reflect the views of Engender, and all language used is the author’s own. Bloggers may have received some editorial support from Engender, and may have received a fee from our commissioning pot. We aim for our blog to reflect a range of feminist viewpoints, and offer a commissioning pot to ensure that women do not have to offer their time or words for free.

Interested in writing for the Engender blog? Find out more here.

Supreme Court Judgment

At Engender it will take us time to fully assess the implications of the lengthy and complex judgment released today by the Supreme Court. We will share further reflections in due course..png)

From our initial reading, we are disappointed that this ruling appears to take a regressive view of the protections provided by the Equality Act. For us, the Equality Act represents the floor and not the ceiling of what we need to achieve on equality as a society. Any backsliding should be of concern to everyone that stands against discrimination and oppression in all its forms.

Generations of feminists have fought against women being defined by our reproductive function and bodies. We will therefore be playing close attention to what this decision will mean in practice for women. As intersectional feminists, we remain concerned about what this means for trans people’s rights. We urge government and public bodies to uphold protections against discrimination and harassment for a group that is facing such misrepresentation and marginalisation in our culture.

Downloads

Engender Briefing: Pension Credit Entitlement Changes

From 15 May 2019, new changes will be introduced which will require couples where one partner has reached state pension age and one has not (‘mixed age couples’) to claim universal credit (UC) instead of Pension Credit.

Engender Briefing: Pension Credit Entitlement Changes

From 15 May 2019, new changes will be introduced which will require couples where one partner has reached state pension age and one has not (‘mixed age couples’) to claim universal credit (UC) instead of Pension Credit.

Engender Parliamentary Briefing: Condemnation of Misogyny, Racism, Harassment and Sexism

Engender welcomes this Scottish Parliament Debate on Condemnation of Misogyny, Racism, Harassment and Sexism and the opportunity to raise awareness of the ways in which women in Scotland’s inequality contributes to gender-based violence.

Engender Parliamentary Briefing: Condemnation of Misogyny, Racism, Harassment and Sexism

Engender welcomes this Scottish Parliament Debate on Condemnation of Misogyny, Racism, Harassment and Sexism and the opportunity to raise awareness of the ways in which women in Scotland’s inequality contributes to gender-based violence.

Gender Matters in Social Security: Individual Payments of Universal Credit

A paper calling on the Scottish Government to automatically split payments of Universal Credit between couples, once this power is devolved to the Scottish Parliament.

Gender Matters in Social Security: Individual Payments of Universal Credit

A paper calling on the Scottish Government to automatically split payments of Universal Credit between couples, once this power is devolved to the Scottish Parliament.

Gender Matters Manifesto: Twenty for 2016

This manifesto sets out measures that, with political will, can be taken over the next parliamentary term in pursuit of these goals.

Gender Matters Manifesto: Twenty for 2016

This manifesto sets out measures that, with political will, can be taken over the next parliamentary term in pursuit of these goals.

Scottish NGO Briefing for UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women

Joint briefing paper for the UN Rapporteur on Violence Against Women.

Scottish NGO Briefing for UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women

Joint briefing paper for the UN Rapporteur on Violence Against Women.

Newsletter

Sign up to receive our newsletter here:

Sign up to our mailing list

Receive key feminist updates direct to your inbox: