Engender blog

Guest Post: Gen Z, the promise of progress, and the persistence of patriarchy

Against the backdrop of the rise in online misogyny and far-right politics, young women are increasingly concerned about a regression in their human rights. In this guest blog, MSc student Matilda Fairgrieve interrogates Gen Z’s socially active image and shares her perspective as part of a digitally divided generation.

-700.png)

Folk are fascinated by Generation Z and our many nuances.

Media outlets fiercely debate our stereotypes; from digital addicts to digital activists, the generation to which I belong is a subject of collective curiosity.

Public commentary often considers our social conscientiousness, ‘changing the workplace and culture as we know it.’ We are viewed as radical, curious and progressive; seldom are we interrogated further. But are we really this way?

Here, I explore this perception of my generation and alert attention to where assumptions of progressive attitudes demand questions – gender equality.

57% of Gen Z men believe women’s equality has gone so far that it discriminates against men. This finding is not in isolation; with another 32% of young men believing gender equality has negatively impacted men. In this context, I position myself among the 59% of my generation who believe there is tension between men and women.

57% of Gen Z men believe women’s equality has gone so far that it discriminates against men. This finding is not in isolation; with another 32% of young men believing gender equality has negatively impacted men. In this context, I position myself among the 59% of my generation who believe there is tension between men and women.

Countless research studies and media outlets will tell you of this “tension” between Gen Z men and women. But how does this tension translate? Trepidation, as Gen Z women ponder these statistics, perplexed. How can it be that such a staggering proportion of young men we share space, workplaces and relationships with hold these views? Despite our disbelief in the percentages, there is no doubt about the problems and pain we’ve experienced as a result. A society entrenched in unequal power, from underrepresentation in politics and leadership, persistent gender pay and pension gaps, disproportionate burden of care as the norm and the violence against women and girls (VAWG) epidemic.

Intergenerationally, there is some difference in how men and women identify as feminists. However, Generation Z’s Millennial, Gen X, and Baby Boomer counterparts are not nearly as divided on the overarching importance of gender equality. Could Gen Z simply grow out of this divide? Debatable when contemplating the socio-cultural realm Gen Z grew into.

Gen Z: The distinct divide

Unique to Gen Z’s divide is the danger lurking in the digital. It is no coincidence that a generation of men aged in a media-fuelled weaponisation of masculinity are threatened by gender equality. Research correlates the self-assessed importance of masculine identity with lower support for gender-equitable policy. Disconcerting political support compounds disconcerting narratives held by young men. Misogynistic and even incel ideologies have crept into dominance, such as 53% of young men believing women are only attracted to a “certain subset of men.”

Unique to Gen Z’s divide is the danger lurking in the digital. It is no coincidence that a generation of men aged in a media-fuelled weaponisation of masculinity are threatened by gender equality. Research correlates the self-assessed importance of masculine identity with lower support for gender-equitable policy. Disconcerting political support compounds disconcerting narratives held by young men. Misogynistic and even incel ideologies have crept into dominance, such as 53% of young men believing women are only attracted to a “certain subset of men.”

As manipulative media actors exploit tensions, isolation among young people is accelerating. 19% of young adults reported having no one they can count on socially. The most digitally connected generation exists in a remarkably distrusting, detached state.

While digitally destructive shifts did not shape the playgrounds of Gen Z’s infancy, I’d argue that a physical shift in our playgrounds set a precedent for disconnect. Gen Z’s early 2000s upbringing coincided with the introduction of Multi-Use Games Areas (MUGAs) in public parks. Open outdoor spaces, a place for equal play, became unprotected from gender roles and division, with boys making up 90% of MUGA usage.

My friends and I shared a similar sentiment to that uncovered in research: “there is nothing stopping us going through the gates of MUGAs, but we don’t feel we should.” From divided children to digital teens – the trajectory of gendered socialisation for Gen Z was fundamentally different.

Reflecting on our unique transition into the digital age with little protection, Gen Z women and I question what this means for present gender equality. With real-world implications of misogynistic digital narratives in corporate and political fields already evident, the time to ask is now.

Building bridges to connect: Real-world gender equity

If Gen Z’s polarisation is a partial result of our upbringing, there is hope for progress in remedying social disconnection and in intervening with the voices that use it as a weapon. Without minimising the complexity we face, the courage to connect and build a bridge rather than a wall certainly feels like a place to begin.

If Gen Z’s polarisation is a partial result of our upbringing, there is hope for progress in remedying social disconnection and in intervening with the voices that use it as a weapon. Without minimising the complexity we face, the courage to connect and build a bridge rather than a wall certainly feels like a place to begin.

Of course, bridges must be built from primary prevention. While the ideological divide of Gen Z men and women may have been digitally fuelled, it was made possible by the root cause of gender inequality. The grip of misogynistic media would not be so tight in a gender-equal, real world.

It is promising to see primary and secondary prevention work picking up much-demanded acceleration in Scotland through initiatives such as the Equally Safe at School and Equally Safe at Work programmes, both shaped by a gendered understanding of the root cause of VAWG. Inspiring work to rectify early disconnects is on the rise, too, with the Make Space for Girls campaign ensuring gender mainstreaming in public spaces for play.

However, the current division between Gen Z men and women requires additional tertiary prevention, acknowledging that these attitudes are already abundant.

To my fellow Gen Z men and women, I’d like to meet outside of the digital world. In-person dialogue, focused on listening to lived experiences and restorative approaches to harm, moving from individual fear to collective security.

Do so with enough meaningful intent, and I’d like to believe our perceived progressive nature will not require interrogation. Building a bridge, together, that serves not only to connect once again, but provide an exit pathway from polarisation and a route to a gender-equitable future.

This guest blog was submitted by Matilda Fairgrieve (she/her), a Gen Z intersectional feminist and MSc student in Political Communications and Public Affairs, inspired by the drive to grow into a gender-equitable future in Scotland.

Guest posts do not necessarily reflect the views of Engender, and all language used is the author’s own. Bloggers may have received some editorial support from Engender, and may have received a fee from our commissioning pot. We aim for our blog to reflect a range of feminist viewpoints, and offer a commissioning pot to ensure that women do not have to offer their time or words for free.

Interested in writing for the Engender blog? Find out more here.

3 Steps to Achieving Primary Prevention in Public Transport

We’ve launched our new series of mini-briefings shining a spotlight on how to achieve a primary prevention approach in different areas of public policy with this new briefing highlighting why safe and accessible public transport is key to gender equality and preventing violence against women.

Public transport isn’t just a matter of convenience; for many women, it’s a lifeline that opens doors to education, employment, and essential services, all of which impact gender equality.

However, Scotland’s public transport system fails to serve women’s distinct travel needs, limiting their access to these opportunities and reinforcing gender inequality. Without changes, these limitations keep women from fully participating in society, impacting everything from their financial independence to safety and personal well-being.

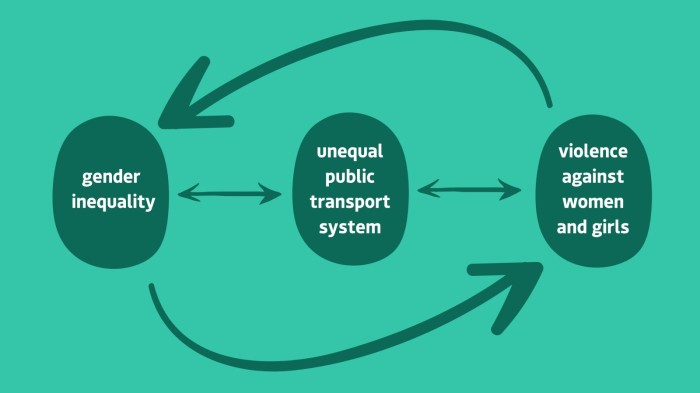

When we talk about primary prevention of VAWG, we’re talking about preventing this violence from happening in the first place. Evidence shows the best way to do this is to tackle the root cause of this violence: gender inequality. Therefore, creating a safe, sustainable and accessible public transport system for everyone is essential for advancing women’s equality and preventing VAWG once and for all.

When we talk about primary prevention of VAWG, we’re talking about preventing this violence from happening in the first place. Evidence shows the best way to do this is to tackle the root cause of this violence: gender inequality. Therefore, creating a safe, sustainable and accessible public transport system for everyone is essential for advancing women’s equality and preventing VAWG once and for all.

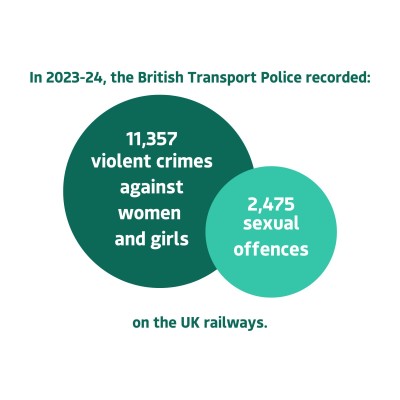

Without safe and accessible transport options, women’s access to critical economic and social opportunities is limited, reinforcing gender inequality, which ultimately enables VAWG. Women’s safety on public transport remains a significant concern and barrier to women’s mobility, due to things like lack of regular and reliable services, design of vehicles and transit points, and insufficient staffing levels.

Our new briefing highlights Three Steps Towards Achieving a Primary Prevention Approach in transport Policy

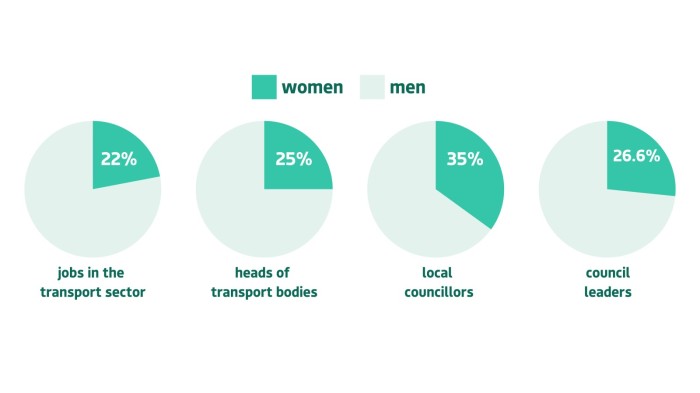

1. Women are equally and fairly represented in policy-making roles

- Improve pathways for women, particularly minoritised women, into the transport sector and career progression opportunities

- Ensure inclusive working environments in the transport sector by implementing flexible working procedures, anti-discrimination and harassment policies and women’s leadership initiatives

2. Policymakers consistently apply intersectional gender analysis in their work

- Collect intersectional gender-sensitive sex-disaggregated data on women’s travel patterns, safety and satisfaction

- Conduct Equality Impact Assessments at the outset of transport policy development to ensure this informs policy and planning decisions at all stages

3. Policymakers mainstream primary prevention in all areas of their work

- Increase opportunities for co-designing transport strategies with women, especially those with lived experience of VAWG on public transport

- Embed women’s safety considerations into transport planning, including in decisions on service provision, the design of infrastructure and staffing levels

Find out more in our new briefing here and follow us on social media to get the latest news on other briefings in the series on housing and planning, coming soon!

GUEST POST: Feminist urbanism: Creating gender-equal cities in Scotland

Engender and the Equal Media and Culture Centre for Scotland have hosted student placements from the MSc in Social Research at the University of Edinburgh and the University of Strathclyde Applied Gender Studies and Research Methods course. As part of their research outputs, the students have produced a series of blogs.

In this post, Beth looks at how women and men experience public space and urban environments and how we can create gender-equal cities in Scotland.

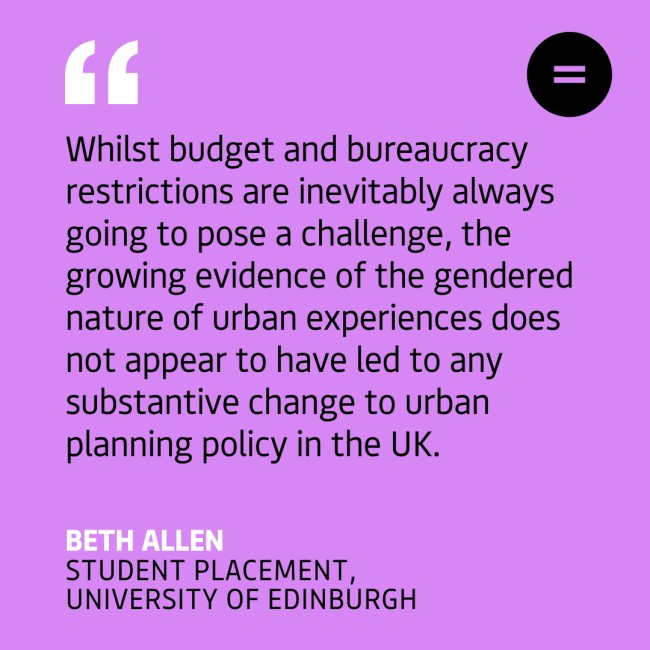

When considering issues of gender inequality, one aspect that is perhaps far subtler and more discrete than others is the way in which the built environment is experienced differently by men and women.

In recent decades, feminist research has studied this phenomenon, with the evidence undeniably pointing to women being disadvantaged in their use of urban spaces. From a lack of accessible and functional public toilets, which biologically women require greater use of, to transport systems that are not built for a purpose beyond that of a daily office commuter, a range of factors have been demonstrated to restrict women’s access to the cities.

GUEST POST: Digital abuse against feminist scholars: a case study

Engender and the Equal Media and Culture Centre for Scotland have hosted student placements from the MSc in Social Research at the University of Edinburgh and the University of Strathclyde Applied Gender Studies and Research Methods course. As part of their research outputs, the students have produced a series of blogs.

In this post, Yoke explores a case study of the online backlash and digital abuse experienced by feminist researchers and scholars.

![The graphic shows a light blue background with white left-aligned text quote that reads "Research has shown that when women speak publicly about ‘controversial’ topics, such as feminism, this triggers online abuse. [...] These attacks must be recognised as part of a historical pattern of violent repercussions against those who defy patriarchal, white supremacist, capitalist dominance.". The quote is attributed to Yoke Baeyens, Student Placement, University of Strathclyde. In the top right-hand corner of the graphic there is the Equal Media and Culture Centre logo.](/siteimages/Blog/yoke-blog-2.png)

Online abuse is used as a silencing mechanism against women and other minoritised identities in the public (online) space.

Weaponising misogyny and dehumanisation techniques, perpetrators aim to push their targets outside the public sphere, to reinstate misogynistic, heteronormative dominance. These public displays of violence also serve to remind and threaten others who might want to defy misogynist, white supremacist, and heteronormative power structures. As Gosse et al. (2021) state, online abuse causes scholars and journalists to self-censor and choose ‘safe’ topics to discuss publicly in an attempt to protect themselves, thereby upholding the status quo. Indeed, research has shown that when women speak publicly about ‘controversial’ topics, such as feminism, this triggers online abuse. This is particularly a problem for feminist scholars who use social media to spread information on feminist research. These attacks must be recognised as part of a historical pattern of violent repercussions against those who defy patriarchal, white supremacist, capitalist dominance. Women have always been the target of abuse, and while the medium is new and everchanging, the intention is not.

GUEST POST: 'Text me when you're home!'

Today we're publishing the first in a series of blogs from the Spring student placements Engender hosted from the University of Strathclyde Applied Gender Studies and Research Methods course.

In this post, Marianne looks at how gender inequality and violence against women affect how women experience public spaces and public transport, and how and when these issues are recognised in the Scottish Parliament.

Keys between knuckles, hair down, earphones out. A routine all too familiar to a woman travelling home after sunset alone.

A male friend once told me that him and his flatmates had a ‘72-hour rule’; if one of them didn’t come home without telling the others where they were, they would wait 72 hours before ‘overthinking’ it and calling the police. I can’t speak for all women, but personally, if it was my female flatmate or friend, it would be at most 12 hours before the panic would set in and a further 12 before I would call the police. Women do not have the luxury of not taking precautions when commuting late at night. Travelling from A to B is necessary in many circumstances, and safety when doing so should be a given, but it is not.

Downloads

Engender Briefing: Pension Credit Entitlement Changes

From 15 May 2019, new changes will be introduced which will require couples where one partner has reached state pension age and one has not (‘mixed age couples’) to claim universal credit (UC) instead of Pension Credit.

Engender Briefing: Pension Credit Entitlement Changes

From 15 May 2019, new changes will be introduced which will require couples where one partner has reached state pension age and one has not (‘mixed age couples’) to claim universal credit (UC) instead of Pension Credit.

Engender Parliamentary Briefing: Condemnation of Misogyny, Racism, Harassment and Sexism

Engender welcomes this Scottish Parliament Debate on Condemnation of Misogyny, Racism, Harassment and Sexism and the opportunity to raise awareness of the ways in which women in Scotland’s inequality contributes to gender-based violence.

Engender Parliamentary Briefing: Condemnation of Misogyny, Racism, Harassment and Sexism

Engender welcomes this Scottish Parliament Debate on Condemnation of Misogyny, Racism, Harassment and Sexism and the opportunity to raise awareness of the ways in which women in Scotland’s inequality contributes to gender-based violence.

Gender Matters in Social Security: Individual Payments of Universal Credit

A paper calling on the Scottish Government to automatically split payments of Universal Credit between couples, once this power is devolved to the Scottish Parliament.

Gender Matters in Social Security: Individual Payments of Universal Credit

A paper calling on the Scottish Government to automatically split payments of Universal Credit between couples, once this power is devolved to the Scottish Parliament.

Gender Matters Manifesto: Twenty for 2016

This manifesto sets out measures that, with political will, can be taken over the next parliamentary term in pursuit of these goals.

Gender Matters Manifesto: Twenty for 2016

This manifesto sets out measures that, with political will, can be taken over the next parliamentary term in pursuit of these goals.

Scottish NGO Briefing for UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women

Joint briefing paper for the UN Rapporteur on Violence Against Women.

Scottish NGO Briefing for UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women

Joint briefing paper for the UN Rapporteur on Violence Against Women.

Newsletter

Sign up to receive our newsletter here:

Sign up to our mailing list

Receive key feminist updates direct to your inbox: