Engender blog

Before the Ballot - Why Candidate Assessment is a crucial step on the journey to more equal representation in politics

With partners in the Equal Representation Coalition, Engender is launching a brand new chapter of the Equal Representation in Politics Toolkit focusing on Candidate Assessment. Ahead of the Scottish Parliament and Local Council elections in 2026 and 2027, now is the time for parties to review how aspiring candidates gain approval to stand if we're to see more diversity on the ballot. Our Development Officer for Equal Representation, Jessie Duncan, explains how the new Toolkit chapter can help.

Before the ballot

When we think about how to make councils and parliaments more representative of the communities they serve, we normally think about elections. How do we elect more women, more minority ethnic people, more disabled people and more LGBTI people? The ultimate decision about who makes it off the ballot and into our councils and parliaments, of course, rests with voters. But in reality, so much about elections is already decided long before polling day. Parties largely have control over who makes it onto the ballot, with many decisions taken in the months and years leading up to election day, shaping the outcome before any votes have been cast.

Parties decide who becomes a candidate through the process of candidate selection. Selection is where the party decides on who from a list of nominees will become the party candidate at the upcoming election. There is a lot of evidence showing the positive impact that using different policies, such as voluntary quotas during selection, can have on the diversity of elected representatives. However this is only useful if there is a diverse pool of potential candidates available to choose from.

Candidate assessment and discrimination

Not just anyone is allowed to put themselves forward for selection - aspiring candidates will usually have to gain the party's approval. This process is known as candidate assessment (sometimes called vetting, screening or shortlisting), and it is at this stage that the first decisions about who our elected representatives will be are taken. Processes vary but usually involve some combination of written application form, an interview with a panel , and might include a test before a final decision is made. Some parties might use these stages to filter, and just like any recruitment process, without consideration of how to combat discrimination and to ensure equal access, candidate assessment risks stifling a more equal, representative politics right at the outset.

Chronic underepresentation – It's not good enough

Unfortunately, no robust data that would tell us about the protected characteristics of our elected representatives is published at the moment, but what we do know tells us that across our councils and parliaments, underrepresentation of marginalised groups is rife – for instance, women make up approximately just 35% of councillors in Scotland, and it took until 2021 for the first two women of colour to be elected to the Scottish Parliament. This kind of chronic underrepresentation benefits no one – we know that when there is meaningful diverse representation, better decision-making follows. Parties have a tremendous responsibility to their membership and to the communities they seek to serve to ensure that candidate assessment processes do not enable and reward only those whose experiences and pathways to politics conform to an outdated status quo of what makes a politician – because it's clear that the status quo is broken.

What will help?

While progress on increasing diversity is often focused on electoral outcomes, to ensure that progress at the ballot box is sustainable, it's essential to look at all stages of the journey and to invest in developing a strong, diverse pipeline of future candidates. This means considering how potential candidates are developed, supported and assessed. As well as being a responsibility, this offers parties a huge opportunity to put into practice often-stated principles when it comes to building a fairer, more equal society.

Parties must ask themselves:

-

What qualities and experiences do we want to see more of in public life?

-

Is the way we assess potential candidates perpetuating inequality?

-

Are our values as a party reflected in the candidates that we approve to stand?

-

Are we meeting our legal duties to ensure a fair and open process under the Equality Act?

To help answer these questions, we're launching a new chapter of the Equal Representation Toolkit, focused on Candidate Assessment. The chapter is aimed primarily at party members and staff who are involved in assessing candidates or in designing assessment processes. Guidance is given on how to run an inclusive and accessible candidate assessment approach that enables people from a wider range of backgrounds to succeed. This includes looking at things like how to advertise and raise awareness of the assessment process; providing equalities training for people involved in assessment; valuing diverse experience; and how to provide constructive feedback and ongoing support for unsuccessful applicants.

As with the rest of the Toolkit, users are invited to take a self-assessment quiz and receive a bespoke action plan highlighting areas for reflection and recommendations for improvement. The Toolkit is easy-to-use and each chapter takes no more than 5 minutes. We can also offer workshops and 1-2-1 support – please get in touch with us if you're interested.

While all attention may be focused on campaigning for the General Election, it's essential to remember what comes next. We are currently 2 and 3 years out from the next Holyrood and local council elections, but it is likely that the processes which will shape these results will begin much sooner. Candidate assessment is the first in a chain of decisions that determine who our elected representatives will be. It's up to parties to make sure that hopes for greater equality in our democracy are built on strong foundations – starting with asking who is given the chance to be on the ballot.

GUEST POST: “Warning” versus “claiming”: the subtle misogyny in media discourse

Today we're publishing the next in a series of blogs from the current student placements Engender is hosting from the University of Strathclyde Applied Gender Studies and Research Methods course.

Kirsty Rorrison's final post continues research into gender bias in political news reporting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Here, she discusses how male and female politicians are quoted and referenced in the media, and how this language plays into wider patriarchal society. You can read Kirsty's first post here and the second post here.

For my third and final blog post, I want to discuss what my research found about female politicians and their news coverage relating to the pandemic. In my last post, I discussed my findings on journalism and COVID-19 in a more general sense; I showed that the topics reported on and who was writing about them seemed heavily linked with patriarchal gender norms. Now, I want to consider what I learned about women in politics based on their representations in news coverage of the pandemic.

Firstly, I found that male politicians received more mentions than women, and the same men were referenced multiple times. Women received fewer mentions overall and were less likely to be mentioned repeatedly. While I was conducting my research, I realised that it wasn’t sufficient only to employ a quantitative analysis of politicians mentioned according to gender, race, and so on; while this data was certainly helpful, it failed to capture the subtleties and nuance I noticed in the news coverage I was analysing. On the advice of my supervisors, I began to think about the ways in which politicians were being represented when they did appear in the news. Were they quoted directly, indirectly, or not at all? What terminology was used to describe them and their ideas? Just because a politician was mentioned does not mean that they have been mentioned the same way as others.

After consulting Carmen Coulthard’s work on direct and indirect quotations, I realised that men tended to be directly quoted - often extensively. On the other hand, women were directly quoted much less and tended to have their thoughts summarised and shortened by the journalist. For example, I only recorded two instances of First Minister Nicola Sturgeon being directly quoted, while male politicians were consistently given direct quotations. Coulthard argues that we can understand this trend through feminist theory - men’s voices are prioritised, and their opinions are granted respect and trust, and as such, they do not have their ideas rephrased or condensed. On the other hand, women rarely get to express their opinions directly and fully since their authority is not often accepted, and subconsciously it is believed that their ideas can be adequately communicated by others.

In terms of the words used when politicians were mentioned, I found that women were described via less definite terminology than men in politics. For instance, most of the time, men were “saying,” “asserting,” “warning,” and so on. Women, on the other hand, often “claimed,” “suggested,” or “argued.” When I first identified this difference, I didn’t think it was particularly noteworthy. However, as I furthered my reading list, I began to understand the nuances present in this difference. When women are described this way, they are subtly undermined and questioned; a term like “claim” does not indicate certainty but rather a degree of scepticism about what is being said.

On the other hand, language like “warning” suggests a level of trust in the speaker’s authority. When this is considered in the context of our patriarchal society, it becomes clear that gender accounts for these different portrayals of politicians. Women are described using more uncertain language because they are viewed as less competent and less authoritative as a result of their gender; the fact that I recorded these instances multiple times shows that it was a definite pattern rather than an isolated incident. Inversely, men are granted trust and authority to know because they are men - by virtue of their gender and its position within the patriarchy, they are seen to be knowledgeable in whatever they discuss.

With this blog post, I conclude my placement with Engender. It has been a privilege to work with each of my talented and knowledgeable supervisors, and I’ve gained so much from this experience. My research has shown that Scottish news coverage of the coronavirus pandemic is clearly gendered - this relates to what is written about, who is writing about it, and who is mentioned in news stories. In terms of politicians, I have found that men are mentioned more overall and that people of colour in politics are notably underrepresented. I have also seen that the ways in which male and female politicians appear in news coverage are different; while men tend to be directly quoted, women are often indirectly quoted. There were also differences in the language used when men and women in politics were mentioned; while men “warned,” “stated,” or “said” things, women “claimed” and “suggested.”

Overall, gender plays an undeniable part in the ways female politicians are represented (or not represented) in Scottish news coverage of the pandemic, but in order to understand the extent of this difference, I needed to delve deeper than a simple quantitative analysis of appearances. Further work must be done to explore these findings further, and in the future, an intersectional analysis should be employed to account for factors like race and sexuality.

GUEST POST: Who says what? A breakdown of gender bias in news topics and reporting

Today we're publishing the next in a series of blogs from the current student placements Engender is hosting from the University of Strathclyde Applied Gender Studies and Research Methods course.

Today we're publishing the next in a series of blogs from the current student placements Engender is hosting from the University of Strathclyde Applied Gender Studies and Research Methods course.

In the second of three posts, Kirsty Rorrison continues research into gender bias in political news reporting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Here, she looks specifically at the breakdown of bias in topics and authors, as well as whose voices are missing in the reporting of the pandemic. You can read Kirsty's first post here.

As my placement with Engender is nearing its end, I have finally completed my research on gender, COVID-19 and media. In this blog post, I’m going to discuss what I found out in my investigation and why it was crucial that I delved a bit deeper into this topic. As I mentioned in my previous post, my main area of interest in this research has always been the ways in which women in politics are represented. However, I also wanted to look at how other women, and more broadly gender, appeared in news coverage of coronavirus. For this research, I ended up coding 108 news stories. I took note of the topic, the gender of the journalist, and the identity markers of every person mentioned in each article. I wanted to see where gender appeared in news coverage, whether this related to the kinds of topics being discussed, the journalists who wrote about them or the people mentioned in articles. In this blog post, I will outline what my analysis revealed about journalists and news topics - in other words, who is writing, and what are they writing about?

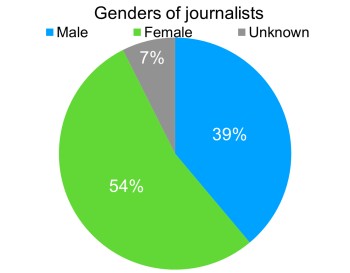

[Figure 1]

I was surprised to find a fairly even split between male and female journalists in my sample [Figure 1]; in fact, women were actually writing about COVID-19 more than men. At first glance, I thought this might suggest that journalism has become more equal in terms of gender. However, upon closer inspection, I realised that things weren’t as progressive as they seemed. While men and women were both reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic, the topics assigned to journalists varied significantly with gender. I found that women were far more likely to cover stories on public health and the NHS than their male counterparts, whereas reporting of politics and economics was often carried out by men. This is consistent with previous work on women in journalism - ‘hard’ news stories relating to industry and politics tend to be given to men, while women are relegated to covering so-called ‘softer’ topics like health, social care and education. This is not true in every case, and I did record instances of women writing about politics and business. However, the general trends I observed speak to wider patriarchal norms in our society, wherein men are respected for technical expertise and intelligence, and women are valued in the realms of emotion, care and nurturing. A breakdown of the article topic by gender of the journalist is shown below [Figure 2].

[Figure 2]

I’d spent quite a while exploring what journalists had been reporting on when I suddenly thought to myself, “what about the topics which aren’t being written about?”. I’d combed through 121 news stories over a seven day period, but I hadn’t encountered anything about domestic violence or caring responsibilities. While these topics hadn’t come up, I’d read multiple articles about planning holidays around travel restrictions. It’s a well-known fact that domestic violence, for instance,

GUEST POST: Looking Deeper: Black and Minority Ethnic Women in the Scottish Parliament

Today we're publishing the next blog in a series from the current student placements Engender is hosting from the University of Strathclyde Applied Gender Studies and Research Methods course.

Today we're publishing the next blog in a series from the current student placements Engender is hosting from the University of Strathclyde Applied Gender Studies and Research Methods course.

Mary Galloway concludes her blog series in this third post, which focuses more deeply on the discussions of Black and minority ethnic women in the Scottish Parliament, and the importance of Parliament understanding the distinct ways that racialised and gendered oppression take shape for different communities. You can read Mary's first post here and second post here.

In this final blog, I will carry out a more focused analysis of the results produced by my research into the representation of women facing multiple discriminations in the Scottish Parliament. I have so far talked about 'women with multiple protected characteristics' quite abstractly. It is important to think about who these women actually are and why it matters that the multiplicity of their marginalisation is acknowledged. Black and minority ethnic (BME) women face both gendered and racial oppression, providing them with experiences that are distinct from white women and Black men. For example, Black and minority ethnic women were some of the worst affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. For this reason, it is crucial that the Scottish Parliament is attentive to the specific needs of this group.

In my search of the content of Scottish Parliamentary business during its 5th session, I used search terms of 'Black women', 'Asian women', 'women of colour', 'BME women' and 'Black and minority ethnic women'. The search term that produced the majority of results for this category of women was the latter term of Black and minority ethnic women. Though this term is importantly inclusive of the diverse ethnicities of women in Scotland, its domination in the results also displays a degree of homogenisation. The needs of Asian women and Black women are not necessarily symmetrical; for example, forced marriage and 'honour’-based violence are forms of abuse that particularly affect Asian women. Consequently, although Black and minority ethnic women all face racialised and gendered oppression, it is important that the distinct way that these take shape for different communities is discussed and understood in Parliament.

A number of BME women's issues were covered in the various areas of parliamentary business. For example, there was recognition of the disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 on Black and minority ethnic women and the prevalence of workplace harassment and discrimination against them. Upon comparing the content of the remarks made by MSPs versus witnesses in the Official Report, there was a notable difference. Witnesses' mentions of Black and minority ethnic women tended to be highly detailed and substantive, whereas MSPs' references tended to go no further than a nod to the difficulty of BME women's lives and calls for more diverse representation generally. MSPs' discussions of BME women were largely quite shallow despite the richness of witnesses' evidence. Furthermore, often when BME women were mentioned by MSPs, they were listed alongside a number of other marginalised women. For example, in a Meeting of the Parliament on International Women's Day 2020, Alison Johnstone of the Scottish Greens said that Parliament should tackle the harassment of women of colour, LBT (lesbian, bisexual, transgender) women, disabled women and refugee women in the workplace. Although this is a very important problem facing women with multiple protected characteristics worthy of discussion, it does not pay attention to the specific discrimination of BME women that is both racialised and gendered. This illustrates a lack of engagement with the fundamental notion that underpins intersectionality, whereupon the needs of communities with multiple protected characteristics are specific and in need of concentrated attention. It is consequently important for MSPs to make the most of the information provided to them by witnesses and their constituents about the reality of BME women's lives in order to affect change in their favour.

This focused look at the case of BME women has provided an insight into the details behind the numbers provided in previous blogs. Such an examination is vital as it uncovers not just how often women with multiple protected characteristics are being mentioned but what is actually being said in these instances. The discussion of Black and minority ethnic women must not be a tick-box exercise, and neither should the discussion of any women facing multiple discriminations.

GUEST POST: Who are the conversation starters in the Scottish Parliament when it comes to marginalised women?

Today we're publishing the next blog in a series from the current student placements Engender is hosting from the University of Strathclyde Applied Gender Studies and Research Methods course.

In Mary Galloway's second post, she builds on her research into how often multiply marginalised women are mentioned in the Scottish Parliament. Here, she looks more closely at who is starting these conversations and why this further calls for more diverse representation in Parliament. You can read Mary's first post here and third post here.

Downloads

Engender Briefing: Pension Credit Entitlement Changes

From 15 May 2019, new changes will be introduced which will require couples where one partner has reached state pension age and one has not (‘mixed age couples’) to claim universal credit (UC) instead of Pension Credit.

Engender Briefing: Pension Credit Entitlement Changes

From 15 May 2019, new changes will be introduced which will require couples where one partner has reached state pension age and one has not (‘mixed age couples’) to claim universal credit (UC) instead of Pension Credit.

Engender Parliamentary Briefing: Condemnation of Misogyny, Racism, Harassment and Sexism

Engender welcomes this Scottish Parliament Debate on Condemnation of Misogyny, Racism, Harassment and Sexism and the opportunity to raise awareness of the ways in which women in Scotland’s inequality contributes to gender-based violence.

Engender Parliamentary Briefing: Condemnation of Misogyny, Racism, Harassment and Sexism

Engender welcomes this Scottish Parliament Debate on Condemnation of Misogyny, Racism, Harassment and Sexism and the opportunity to raise awareness of the ways in which women in Scotland’s inequality contributes to gender-based violence.

Gender Matters in Social Security: Individual Payments of Universal Credit

A paper calling on the Scottish Government to automatically split payments of Universal Credit between couples, once this power is devolved to the Scottish Parliament.

Gender Matters in Social Security: Individual Payments of Universal Credit

A paper calling on the Scottish Government to automatically split payments of Universal Credit between couples, once this power is devolved to the Scottish Parliament.

Gender Matters Manifesto: Twenty for 2016

This manifesto sets out measures that, with political will, can be taken over the next parliamentary term in pursuit of these goals.

Gender Matters Manifesto: Twenty for 2016

This manifesto sets out measures that, with political will, can be taken over the next parliamentary term in pursuit of these goals.

Scottish NGO Briefing for UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women

Joint briefing paper for the UN Rapporteur on Violence Against Women.

Scottish NGO Briefing for UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women

Joint briefing paper for the UN Rapporteur on Violence Against Women.

Newsletter

Sign up to receive our newsletter here:

Sign up to our mailing list

Receive key feminist updates direct to your inbox: